Preying On Innocence

The Bois Locker Room Case has brought to light increasing cases of online child abuse. And social media can be held liable under Section 20 of the POCSO Act and the IPC for such content.

May 28, 2020, 1:25 pm

By Dr Vidyottma Jha

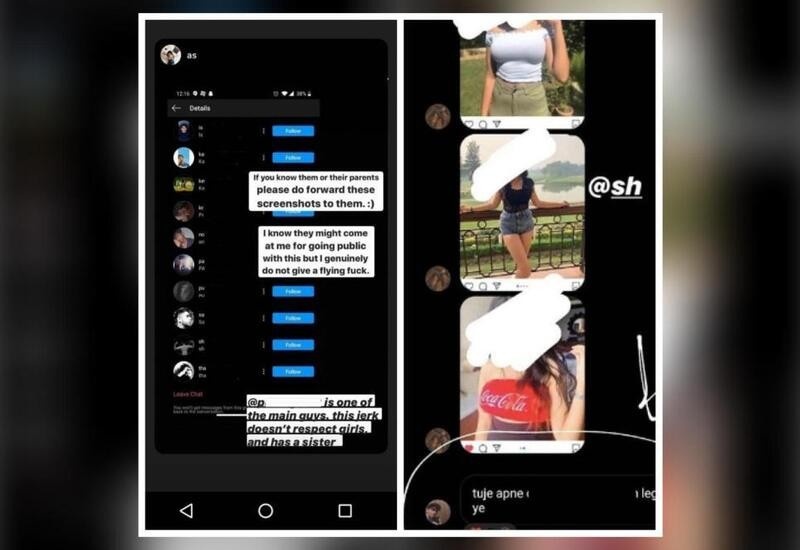

The recent Bois Locker Room case where disturbing tweets and Instagram posts were shared about minor girls has brought to light increasing cases of child abuse. An all- boys group chat was created on Instagram with around 100 members, all boys from South Delhi, which was made to send objectionable pictures of minor girls, morphing them, using abusive language and talking about gang raping them.

Child sexual abuse is a form of abuse where an adult or older adolescent uses a child for sexual stimulation. Various forms of child sexual abuse include engaging in sexual activities with a child whether by asking, pressuring or indecent exposure. In fact, sexual violence against children is a gross violation of their rights. Yet, it is a global reality which can also take the form of sexual abuse, harassment, rape or sexual exploitation by prostitution or pornography. It can happen in homes, institutions, schools, workplaces and within communities.

The increasing use of the internet and mobile phones has put children at risk of sexual violence and the number and circulation of images of child abuse have risen. In fact, children themselves forward each other’s sexualised messages or images. This “sexting” puts them at risk for abuse.

With the lockdown due to Covid-19, children are spending more time online, which has aggravated the rate of crimes against them. A report released by Europol titled “Pandemic Profiteering” stated that there is an increase of online activity by those who are seeking child abuse material. The report found a correlation between this being consistent with online postings in forums by offenders.

PORNOGRAPHY

Pornography is a depiction of sexual behaviour through books, pictures, statues, motion pictures and other media and intends to cause sexual excitement. The word pornography, derived from the Greek porni (“prostitute”) and graphein (“to write”), was originally defined as any work of art or literature depicting the life of prostitutes.

Pornography can be divided into two categories—child pornography and adult pornography. Child pornography has two basic contents:

i. Oral communication about sex

ii. Sending the child pornographic data.

Pornographic images and films became even more widely available with the emergence of the internet in the 1990s. The pornography industry became one of the most profitable on the internet. Apart from providing a vast marketplace for commercial pornography, it appealed to many diverse tastes which later added to the increased availability of child pornography. Pornography has long been condemned and legally proscribed in the belief that it depraves and corrupts both minors and adults and leads to the commission of sex crimes.

CYBER CRIME MENACE AND THE LEGAL SCENARIO

Pornography has emerged as a subject of discussion globally. It seems like the worse impact of technology. The free use of the internet has impacted the next generation badly. The Information Technology Act, 2000, Chapter XI in Article 67, clearly mentions online pornography as a criminal offence and carries a jail sentence of up to three years and a fine of up to Rs 5 lakh. The IT Act, under Section 67A, lays down that the publication and transmission of documents in electronic form related to sexually explicit acts or behaviour are punishable with imprisonment up to five years and a fine up to Rs 10 lakh.

The Indian Penal Code, 1860, under Section 293 specifically mentions the law against the sale of obscene objects to minors which pertains to pornography or “obscenity” under Section 293. The Act was amended by the Information Technology Act in 2008 for the inclusion of electronic data. According to the amendment, a section was added which criminalises surfing, downloading and publication of child pornography. Thus, internet pornography can lead to a sentence of five years’ imprisonment and Rs 4 lakh fine.

BOIS LOCKER ROOM CASE

According to the Information Technology Act, 2000, the offences that were committed in this case include using of a fake identity to create an Instagram account. This is punishable by up to three years and a fine up to Rs 1 lakh. Publishing, transmitting or causing the same in electronic form would be liable for imprisonment up to five years and fine up to Rs 1 lakh. Besides this, if it depicts children in an obscene or sexually explicit manner, creates texts or digital images, browses, downloads or exchanges, it would be liable to imprisonment up to five years and a fine up to Rs 10 lakh.

POCSO ACT, 2012

The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012, is an essential piece of legislation that criminalises cybercrime against children, including child pornography, cyber stalking, cyber bullying, defamation, grooming, hacking, identity theft, online child trafficking, online extortion, sexual harassment and violation of privacy. Any person who has knowledge of commission of such an offence or knows that an offence is likely to be committed must report it to the local police and the Special Juvenile Unit under Section 19 of the Act.

LAWS REGULATING SOCIAL MEDIA

The Constitution guarantees to all citizens a number of Fundamental Rights. One of the most important ones is the “Right to freedom of speech and expression” under Article 19 (1)(a). This freedom is not absolute. It is always subject to certain reasonable restrictions which the State may impose in the interest of the citizen or the country. Therefore, even social media is regulated by the Information Technology Act which was enacted to regulate, control and deal with the issues arising out of IT.

Social networking media is an “intermediary” within the Information Technology Act. Thus, in India, this media is liable for various acts or omissions. To add to it, under the Indian Penal Code, there are important sections which could be effective against posting offensive messages on social media. The defamatory statement could be oral or written or in sign language or by visible representation and should be made or published with the intention to harm or with the knowledge of its defamatory character. Section 499, IPC, is wide enough to encompass the publication and dissemination of defamatory content via electronic means. Defamation is punishable under Section 500, IPC.

Further, the law against obscenity is a reasonable restriction on the “fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression”. The Internet facilitates the creation as well as rapid transmission of such material across the world. Legal regulation is complicated by the fact that there is no universally acceptable definition of obscenity. Traditional laws that deal with obscenity, including pornography, are contained in Sections 292-294 of the IPC. Publishing as well as circulating of obscene photographs of women is also punishable under Sections 3 and 4 of the Indecent Representation of Women (Prohibition) Act, 1986. These provisions can also be used for punishing people who circulate obscene material in electronic form.

LIABILITY OF INSTAGRAM

Social media platforms enjoy a safe harbour with respect to online offences. They are considered intermediaries and thus, under Section 79 of the IT Act, are granted conditional immunity from liability for third party acts. This implies that social media platforms are merely a facilitator of communication and do not have any “knowledge nor control” over the information transmitted through them.

This issue was highlighted in Ashish Bhalla vs. Suresh Chaudhary, where group administrator WhatsApp was made party to a suit regarding a defamatory post. The Delhi High Court held that the administrator could not be held liable for defamatory statements made on the group.

The reason cited was that members can make posts on the group without the approval of the administrator. The Court observed that holding the administrator accountable for such content was the equivalent of making the manufacturer of newsprint on which defamatory statements are published liable for defamation.

Despite having this judgment as a precedent, the gravity of the offence and its seriousness cannot be ignored. Even with the provision of safe harbour protections, Instagram can still be held liable under Section 20 of the POCSO Act.

The Act requires any personnel of the media or other groups to file a complaint with the Special Juvenile Police Unit or the local police whenever they come across any such content. The Delhi Commission for Women has also taken suo motu cognisance of the Bois Locker Room case and issued a notice to Instagram asking it about the action taken by them against the alleged abuse.

REPORTING OF CYBER OFFENCES

In a maiden initiative by the government, it has started a portal to facilitate complaints about cyber crimes online. This portal caters to complaints pertaining to online child pornography (CP), child sexual abuse material or sexually explicit content such as rape/gang rape (RGR) content and other cybercrimes such as mobile crimes, online and social media crimes, online financial frauds, ransomware, hacking, cryptocurrency crimes and online cyber trafficking.

The portal also provides the option of anonymously complaining about online CP or sexually explicit content such as RGR content.

Thanks to the pandemic, there has been an unprecedented rise in screen time. Families worldwide are relying on technology and digital solutions to keep children learning, entertained and connected to the outside world. Spending more time on virtual platforms can leave children vulnerable to online sexual exploitation and grooming as predators look to exploit the pandemic for their benefit. A lack of face-to-face contact with friends and partners may lead to heightened risk-taking such as sending sexualised images, while increased and unstructured time online may expose children to potentially harmful and violent content as well as put them at a greater risk of cyber bullying.

“Under the shadow of Covid-19, the lives of millions of children have temporarily shrunk to just their homes and their screens. We must help them navigate this new reality,” said UNICEF Executive Director Henrietta Fore.

A great amount of responsibility now rests on governments and industry to join forces to keep children and young people safe online through enhanced safety features and new tools. Parents and educators need to teach children how to use the internet safely. Children’s rights to privacy and protection should not be compromised.

Moreover, the lockdown is a time for parents to speak to their children about online safety, how to change settings to “private, friends or contacts only”, or prevent spam or unwanted sexual content. Promoting positive online and recreational use and building children’s skills to stay safe online will serve them well after the lockdown is lifted.

—The writer is an advocate in the Supreme Court

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment. Click here to login